- Home

- Kate Pearce

Tempted at Christmas Page 2

Tempted at Christmas Read online

Page 2

“How can you refuse such a pretty invitation?” Grace asked with a smile.

There was nothing for it, of course, except to damn his pride and his promise to stay away from Bocka Morrow and long tall, irresistible Tressa Teague. “When you beg like that, I suppose there is no way for me to refuse. When must I go?”

“Immediately—I’ll convey you back to Bocka Morrow myself in my father’s traveling coach. It’s well sprung and plush, Matts. I intend for us to go out in style.”

If he had to go out, Matthew reckoned there was no damn better way to go, than in style. “Lay on, Becks. Lay on.”

Chapter 4

Village of Bocka Morrow,

Coast of Cornwall

November 23, 1811

Oh, heaven help her. He was here—Captain Matthew Kent was standing in the vestry of St. David’s, not twelve feet from her.

Tressa’s heart slipped and tripped like a maiden aunty drunk on too much elderberry cordial—she had to grip the back of a choir pew to steady herself.

Why had he come? But more to the point, why had no one told her he was coming? And how was it possible that was he standing in the vestry of the church with Papa and Lord Harry, looking for all the world as windswept and gallant as if he had just walked off a quarterdeck in his blue naval dress uniform?

She’d known he was a naval officer, of course—she had easily picked out his military bearing even when he had been disguised as a fisherman—but she’d never seen him in anything but knitted wool jumpers and that battered old sea coat he had worn even when commanding his lugger against the French corvette in Black Cove.

But the contrast of the dark blue coat and the flaming red of his ginger hair was so brilliant it near hurt her eyes to look at him. To say nothing of her heart, which was still somehow pumping—still keeping her alive and capable of some small sort of reason—though she had done her best to turn it to stone.

Captain Kent was no doubt acting in support of his brother officer, while Lord Harry’s real brothers, Anthony, Viscount Redgrave, and Lord Michael, along with his parents, the Marquess and Marchioness of Halesworth, and his recently married sister Charlotte, now Viscountess Lynwood, sat in the front row across from Mama.

Just as Tressa was attending in support of her sister. She had come to the vestry to announce that Nessa was ready at the door of the church, wearing her pretty bridal ensemble of a dress of fine white wool shot with embroidered primrose and white-satin flowers that she had made and embroidered herself so as not to embarrass herself before Harry’s illustrious relations.

But it was Tressa who was now the embarrassment of a bridesmaid, dithering in full view of the assembly. But this was Nessa’s day, and Tressa refused to ruin it by her behavior. “Papa,” she called in the steadiest voice she could find. “Nessa is ready.” And then she hurried away to attend her sister to the altar and see her bestow her hand upon Lord Harry.

And if Captain Kent stood on the other side of the groom, like a tall oaken mast of a man, she would take no notice of him.

She would not.

It was no matter to her that the gold epaulettes on his uniform coat glistened in the sunlight, or that he and Lord Harry together in their blues looked as dashing as dashing could be.

It was no matter than her heart was thumping as if she had raced all the way up to the top of the bell tower of St. David’s, and all the way back down again.

It only mattered that she not embarrass her sister, or do anything to dim her happiness.

A surreptitious glance over her shoulder revealed that a good half of the village seemed to have invited themselves, crowding into the pews at the rear of the church, hanging back for propriety’s sake, but unable—or unwilling—to turn away from the spectacle of one of the vicar’s poor-as-a-churchmouse daughters marrying a lord.

It was every poor village girl’s fantasy, she supposed, to marry a man who could sweep her away from gutting fish and scraping scales, or cooking on an open fire and cleaning the grates of fireplaces, or correcting lessons and writing out sermons.

But Nessa would have loved her Harry if he had only been a sailor. In fact, Tressa would bet both Nessa and Harry would have preferred he be a simple sailor so they could marry with a great deal less pomp and circumstance, even though the wedding was only a simple ceremony in a village church with a wedding breakfast to follow at the vicarage.

But when the “I wills” had been uttered, and the giving and receiving of rings had been exchanged, and the blessing spoken, the crowd of villagers still lingered, following the wedding party across the churchyard and onto the lawn, so that Mama, who could not turn away a chance to show off her daughter, was obliged to invite them all in for a glass of celebratory punch.

In no time, the wedding breakfast had been abandoned in favor of a more informal party that moved easily between the open house and the sunny garden full of autumn color, with avid villagers eager to see the private family rooms of the manse, not just the vicar’s book room.

Even Elowen Gannet—she who had once tried to claim Lord Harry for her own—wandered freely about, though her presence gave Tressa’s new brother-in-law pause.

“Didn’t think to see Miss Gannett here,” Harry confided in a low voice.

“Perhaps she wanted to make sure the deed was well and truly done before she moved along to manipulating some other poor fellow into marriage,” was Tessa’s amused, if cynical take.

“Oh, I think Miss Elowen Gannet has very specific requirement in a husband,” Harry said. “Though I am as glad as I can be that chap isn’t me—gives me the willies, your Miss Gannett does. She’s too bloody ambitious by half—only wanted me to further her scheme to run the smuggling operation in Bocka Morrow without her father’s interference.”

Tressa pricked up her ears at the same time that Nessa shot her a quelling glance. While it was well-known within the family, and perhaps to some others like Joss Williams, the publican of the Crown & Anchor pub down near the quay, it was generally not known that Tressa was, in fact, the one person who managed the bulk of the smuggling operations—at least on the north side of Bocka Morrow. Tressa had never participated in any free trade to the south, where Squire Gannett kept his own caves and used his own workers.

But as little as Tressa knew or liked the Gannets, perhaps the time for keeping quiet and hiding her ambitions was over. “I think I’ll go have a chat with our Ellie.”

Who knew if they might find that some of their schemes for less interference were aligned. And Ellie had lost her bid to snag the very-well-worth-having Lord Harry in an Allantide alliance, so Tressa was prepared to be generous.

Tressa waited for Ellie to take her leave, then she snatched up a woolen shawl from the pegs in the kitchen hall as a preservative against the autumn chill, and followed her out through the orchard path. “Ellie!”

Her call made her quarry stop and glance back. “Tressa.” Ellie acknowledged her with a toss of her chin. “Come to tout your sister’s triumph?”

Tressa shrugged. “If it is a triumph, it’s hers, not mine.”

“Really?” Ellie gave her a long glance out the side of her eye as she tried to gauge Tressa’s tone. “Rumor had it that you and that—”

“Rumor is wrong.” Tressa spoke perhaps more forcefully that she intended—she lowered her voice to a more conversational pitch. “But I’d like to chat about a different rumor I heard—one that told me that you and I are more alike that we might think.”

True to form, Ellie’s glance shifted across the churchyard to where Captain Matthew Kent had just stepped outside into the fall sunshine to talk to the Marquess of Halesworth.

“Not a man, Ellie, but something more important.” Tressa forced her mind away from the distracting captain, and lowered her voice to keep their conversation private. “The free trade.”

Ellie’s eyes sliced back to Tressa, wary and sharp. “What about it?”

“Surely you know that I organize everything for our crews

—unloading, and moving the cargoes on when they come into the north caves?”

“I’ve heard—you keep the tot sheets.”

“Yes.” It was a sop to the men’s pride, that offhand denigration of her true contribution. “And more. I set the crews in the caves. I calculate the price of shares and divvy up the money. I’ve sailed to Guernsey to arrange financing, pick up cargoes and to better understand the system. I decide what goes where up-country—how many bolts of silk and lace go to Leeds or London, how many ankers of brandy go to this inn or that. I was the one to suggest the women be included in moving the goods from the caves into cellars across the countryside, and from there to the inns, taverns and aristocratic wine cellars from Truro to Taunton because farmwives could better evade the Revenue with the ankers up their skirts. I’m the one that has made all the suggestions for improvements over the past few years.” Tressa stopped herself—even she could hear the combination of fierce pride and bitter frustration in her voice. “But that’s all I can do, Ellie—make suggestions. I can’t decide—not on my own.”

Ellie was cautiously curious. “And you think I can?”

“I think you want to.” Tressa took another deep breath. “And I think you could. And so could I—with help.”

Ellie’s voice was quiet. “And you think I would help you?”

“I think we could help each other.”

Ellie thought about that suggestion for a good long while, searching Tressa’s face for any hint of sarcasm or trick.

“I’m in earnest, Ellie. We could do it. But we’ll have to fight for what we want—no one, least of all any of the men in this be-nighted village, is going to give it to us.”

“How will we fight?”

“The way women the world over have always fought—with our wits. We’ll be better, more clever, more efficient—we’ll make more money.”

Ellie’s mouth pursed into a silent “o” of shrewd contemplation. “I’m always after telling my Da we could do it better—ordering a cargo of what we want and need in advance from Guernsey instead of taking whatever comes off the boats.”

Tressa could feel herself smile. “Just so, Ellie. Just so.”

Ellie blew out a little huff of pleased surprise. “Who’d have thought?”

“I did,” Tressa admitted. “I’ve always thought I could do it better.”

“No.” Ellie shook her head but smiled. “Who would have thought of all the people in Bocka Morrow, the one to want to help me take over the smuggling would be the vicar’s daughter. But you always did sit up there in the front row of the church with your family looking like you were a thousand miles away—you and your sister both. Who’d have thought you were thinking of the trade a few miles offshore?”

“I told you—I’m always thinking. Thinking beyond mere smuggling. To a legitimate concern, importing from farther afield—Canary and Sherry wines from Spain—to our west coast.”

“And have you thought of how we’re to even begin to make that happen?”

“Indeed. We need capital. Once we get enough, we’ll run a few smuggled cargoes to build up enough profit to go legitimate, and then—”

A quiet voice broke in. “Well. Tressa and Ellie Gannett. Whatever can you two be talking about?”

Chapter 5

It was the bride, Nessa Teague Beck, accompanied by her new husband Harry, who asked the question. Matthew was only with them because Becks had insisted he meet Nessa’s sister.

Who shot him a look as mean and cutty-eyed as any smuggler might. “Captain Kent.”

“Miss Teague.” He bowed, carefully polite, incredibly wary—every instinct he possessed told him Tressa Teague frankly wished him to perdition. “Miss Teague and I are acquainted.”

He would do everything in his power to act the gentleman, though she looked like she had even less interest in acting the lady than ever—something he said made her head snap back as if she’d taken a hit.

Beside Becks, his new bride laughed. “Yes, Tressa, you are Miss Teague now. Kensa and I relinquish our turns at the title to you—you are no longer Miss Tressa.”

Tressa Teague acknowledged her sister with a nod, and then put her chin up as if she were determined to show that she was not in the least discomfited by the change. “Captain Kent.” She acknowledged him with the barest civility. “Are you acquainted with my friend Miss Gannett? Miss Elowen Gannett, this is Captain Matthew Kent of the Royal Navy frigate, Vanguard, which will very shortly be taking command of the West Indies Squadron.”

Ah. That boded better—though her tone was brisk, she was still enough interested in him to know the particulars of his posting. “I see news travels fast. I’m honored that you would make note of my promotion.”

Tressa Teague gave him a witheringly polite smile. “The announcement was in the newspaper from Truro that we used to wrap the fish.”

The knowledge that she was definitely no longer his friend—and the realization that she might, in fact, be his enemy—was a hit to his pride. “May I speak with you privately, Miss Teague?”

While the others—Becks, his bride and Miss Gannett—looked from one to the other, and waited for Tressa to make him her answer, her gaze never wavered. “I am sure that whatever you have to say to me, Captain Kent, can be said in public.”

“I am equally sure it cannot.” She had tried his civility long enough—he put his hand into the supple small of her back and propelled her away from the others. “The belfry, as I recall, is a private enough place out of the wind.” He ushered her across the chilly churchyard and through the portal. “I take it you still have the key?”

“If I do, I shan’t be persuaded to— Oooh!” She made a sound of embarrassment and outrage that echoed around the church vestibule like a pistol shot when he abruptly took charge by reaching under the modest fichu of her simple but lovely gown—and what a sweep of bluebell-colored wool it took to cover long, tall Tressa Teague’s legs—to fish out the key on the chain hidden down the warm vee of flesh between her breasts.

She was pulled closer, of course, when he fit the key into the lock—so close he could see the care she had taken with her normally indifferent coiffure. So close he could smell that lovely tang of lemon and verbena from her soap.

So close her breath whispered across the back of his hand. “Here,” it whispered. “Here is your woman.”

He did not respond. He could not—she didn’t like him, though she had once kissed him with an enthusiasm he still found heartening.

Matthew let the key go the moment he had unlocked the door and stood back to let her enter the narrow, stone stairway ahead of him. “After you.”

She let the chain back slink back behind the fortress of her high-waisted, devilishly well-fitted bodice before she answered. “You’re not planning to push me off, are you?”

“Not if you don’t tempt me.”

“Clearly, I’ve worn out your charm.” She crossed her hands over her breasts and didn’t move. “Why are you here?”

“To celebrate your sister and Harry’s wedding. I assure you nothing would have persuaded me to disrupt your peace, otherwise.”

“Peace.” Her voice was full of cynical detachment. “But I meant here and now—why do you want to speak to me? And drag me up the belfry? What can you possibly have to say that has not already been said?”

Nothing had actually been said. Nothing. In the aftermath of the battle, he had been consumed by his work—shoring up the damaged French vessel and making arrangement for the hundred or so French sailors they had taken prisoner, as well as formulating his report to the Admiralty—and she had simply disappeared, gone up the quay into the grey mist as swiftly as she had first appeared to him that chilly dawn.

He tried to be his usual, merry, confident self. “I merely wanted to assure myself that you are all to rights—that you had recovered from the ordeal of the battle at Black Cove.”

“As you see.” She spread her hands in front of her skirts in a gesture that was both ope

n and entirely concealing. “And I didn’t think it an ordeal. I told you then, I’m not missish.”

“So you did.” And she had not looked the least bit missish that night with the wind in her teeth and the tiller of his lugger beneath her hands when he had been too engaged with the heat of battle to notice that she had done what needed doing without being asked. She had looked magnificent. “You had a heart of oak that night. I suppose I wanted to make sure it was still beating in tune.”

She swallowed some rising emotion before she said, “Not to your tune, if that is what you meant.”

“No. I—” Damn her eyes, but she had a way of looking at him—as if she saw right through him—that put a man off balance. He knew what to do with a ship—how to order his sails and level his guns against an enemy—but in a drawing room, or even in a bell tower, he felt himself an utter ass. “Come, Teague, I know I left very suddenly, but orders are orders, and—”

“It’s Miss Teague to you, Captain Kent.”

Her prim—yes, missish tone, when she had just said she wasn’t—pushed him a fathom too far. “It wasn’t Miss Teague, or Captain Kent, when you were kissing me, was it?”

The moment the words left his mouth he wished them back. But that was his problem, wasn’t it—acting on the impulse of the moment, instead of weighing things out.

She drew in a sharp breath before she put her chin up even higher. “Were I closer to you, Captain, I would have slapped you. Hard.” Her voice was taut with repressed emotion. “Just because we kissed does not mean you can speak to me in such a manner. Now”—she backed away as if to preserve herself from the temptation, rubbing her hands up and down her arms as if she were suddenly chilled—“say what you brought me here to say, and be done with it before I find myself in any less charity to listen to you.”

A Ghost of a Chance

A Ghost of a Chance The Maverick Cowboy

The Maverick Cowboy And a Pigeon in a Pear Tree

And a Pigeon in a Pear Tree The Rancher Meets His Match

The Rancher Meets His Match A Christmas Brothel: A Set of Canterbury Christmas Tales

A Christmas Brothel: A Set of Canterbury Christmas Tales The Cowboy Lassoes a Bride

The Cowboy Lassoes a Bride The Second Chance Rancher

The Second Chance Rancher Sweet Talking Rancher

Sweet Talking Rancher The Last Good Cowboy

The Last Good Cowboy The Rancher's Redemption (The Millers of Morgan Valley Book 2)

The Rancher's Redemption (The Millers of Morgan Valley Book 2) The Billionaire Bull Rider

The Billionaire Bull Rider The Duke of Debt

The Duke of Debt Death Bringer sj-2

Death Bringer sj-2 Bedeviled

Bedeviled Tempted at Christmas

Tempted at Christmas The Lord of Lost Causes

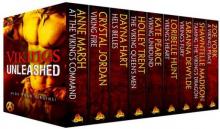

The Lord of Lost Causes Vikings Unleashed: 9 modern Viking erotic romances

Vikings Unleashed: 9 modern Viking erotic romances